the Merion Friends Burying Ground

There are an estimated 2700 graves

In the Burying Ground attached to Merion Friends Meeting. For 82 years, this was the only place in Lower Merion for burials. For most of its history, anyone might be buried there. I conservatively counted 263 Children on the burial record, but some have claimed 20% of the burials are of children.

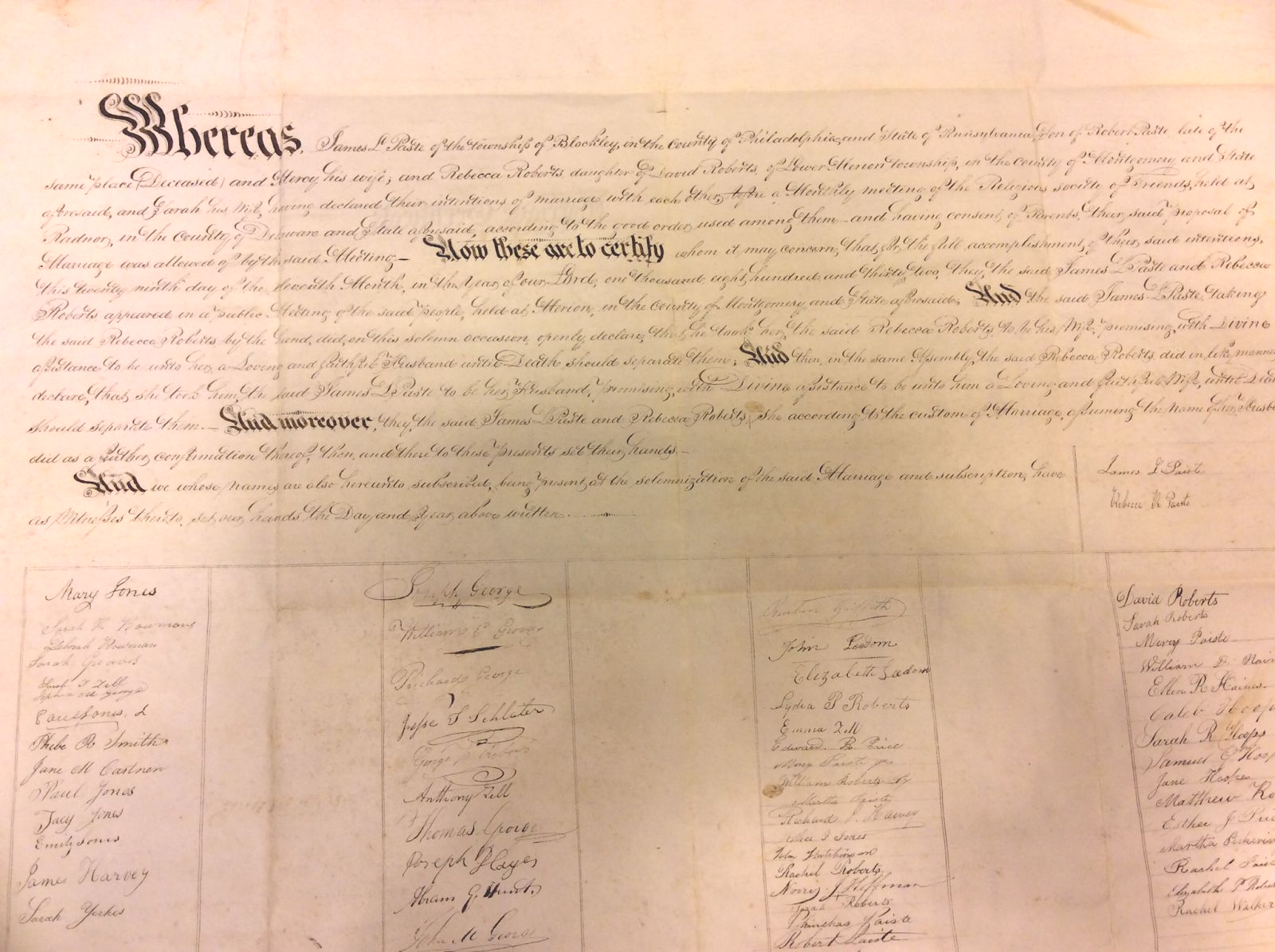

Catherine Reese, a two year old who died soon after the Welsh settlers arrived in 1682, was the first burial in what would later become the cemetery. Thirteen years later, Edward Rees sold 1/2 acre to the Overseers for a burial ground. In the 346 years since, an estimated 2700 burials have been added, mostly Quakers, but also strangers, slaves, casualties from explosions at the powder mills on Mill Creek, and perhaps even Indians. Causes of all deaths are listed as follows: suicide, murder, cholera, yellow fever, tuberculosis, flu, softening of brain (it is unclear

what this referred to—perhaps dementia), consumption, fractured skull, lingering illness, run over by wagon, alcohol, erysipelas, nephritis, myocardial failure, drowning, powder mill blew up, bilious fever, heat prostration, carrying stones at paper mill, falling out of window, cardiovascular disease, covered by snow, cerebral hemorrhage, hives, typhus fever, smallpox, carcinoma of stomach, flux, white swelling (of joints), fall off trestle, stillbirth, fever, lockjaw, poisoning.

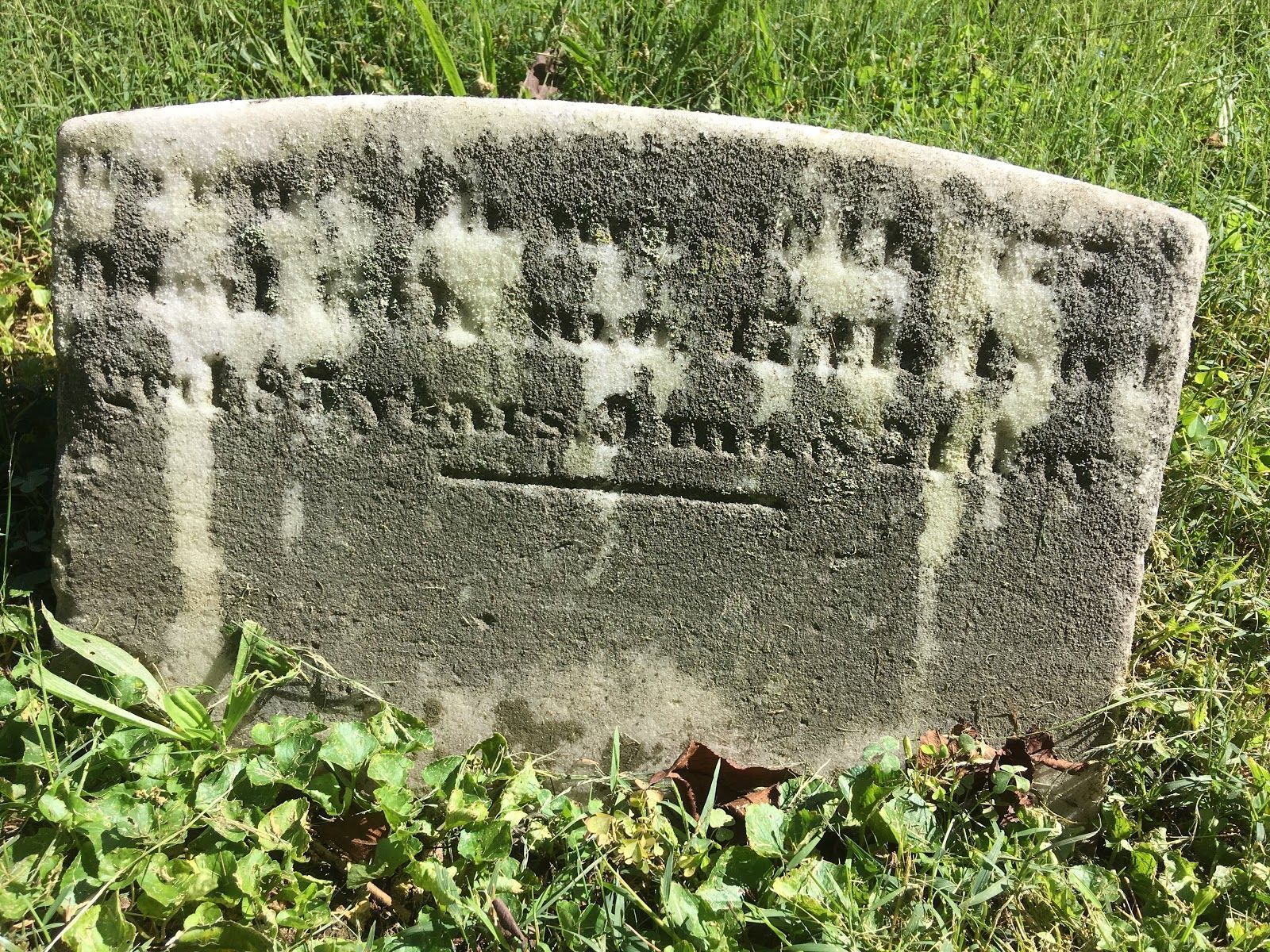

One of the many headstones in the Merion Friends Meeting burying ground

‘I found a number of Friends assembled about the house of the deceased, and waiting in silence for the body to appear. It … was in a coffin of black walnut, without any covering or ornament, bourne by four Friends; [four] women followed, who … were the nearest relatives and grand-children of the deceased* [* None of them were drest in black. The Quakers regard this testimony of grief as childish.] All his friends followed in silence, two by two… There were no places designated; young and old mingled together; but all bore the same air of gravity and attention.’

There are many interesting graves in this cemetary, including sixty-three Revolutionary War veterans.

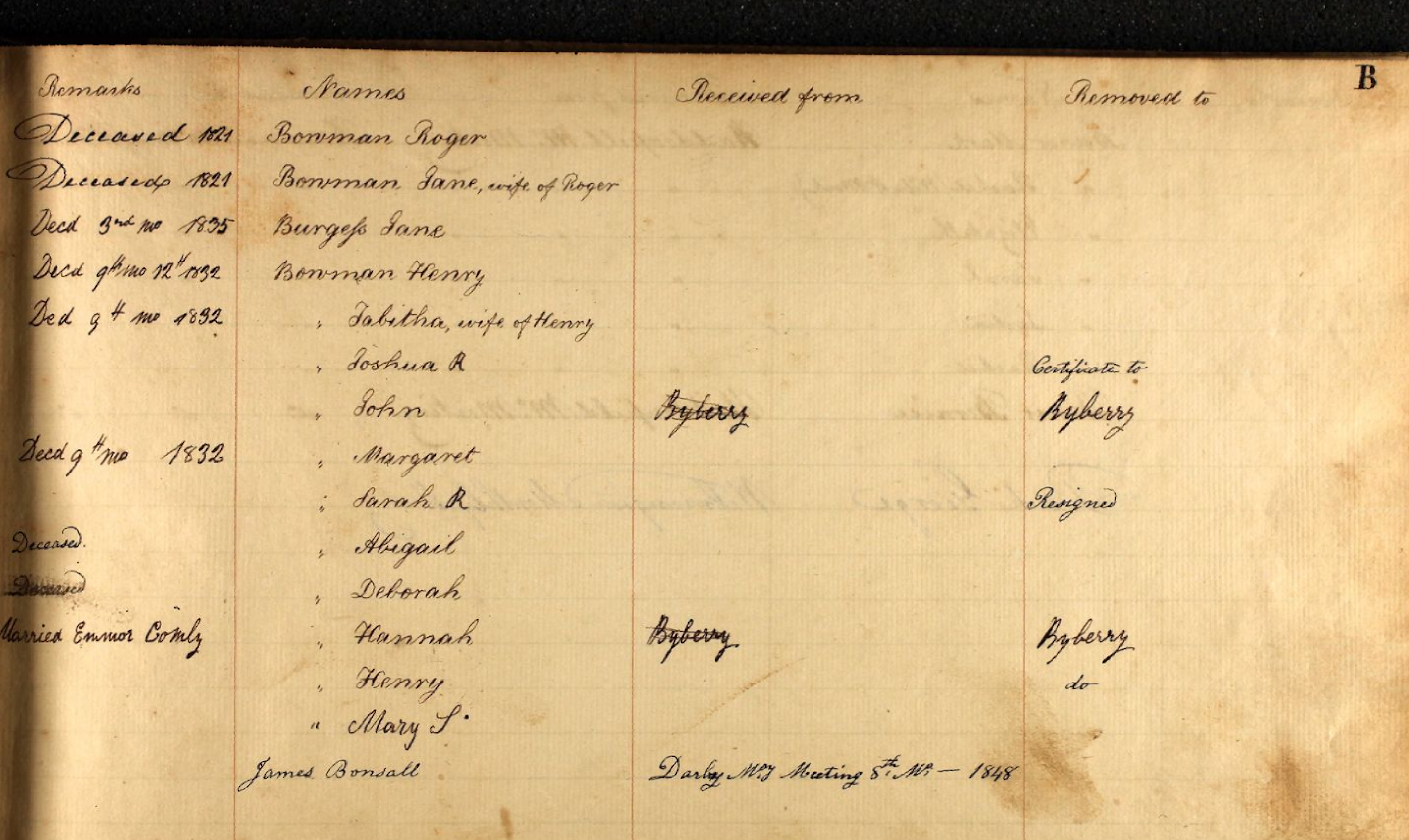

There is a woman who drowned in 1748, and members of the Bowman Family who succumbed an 1832 cholera epidemic.

The oldest grave marker is believed to be that of Rebecca Roberts, who died in 1719.

At least 23 African-Americans are listed on record, some named,

many not. The Erwin family was wiped out by the yellow fever epidemic 1793-94 (6 of them died). Thomas Roberts lost two daughters in summer of 1793. During the week of July 25, 1795 many died.

In 1807, Ann Roberts was murdered by her deranged son.

In the burial record for the Merion Meeting burial ground, there is a listing under Unknown for “Indian, died March 21, 1792, interred with the honors of war” and the source is listed as

“Joseph Price’s Diary, March 22, 1792: “very Great Burial of an Indian, that Dyed, he was one of 50 that came in some little ago, the greatest Geathering of people perhaps Ever Collected on the Like occation, was Interd with the Hons. of war”.

This is the only listing for an Indian--but the burial map puts an Indian at the end of the Zell row.

It sounds like the people who put together the burial record misinterpreted Joseph Price’s diary entry (based on the newspaper account of the burial of an Indian Chief in Philadelphia in 1792 (found by Nancy Webster): “According to the Daily Advertiser (Phila.), a prominent Oneida chief,

one of a delegation to Congress from the Haudensaunee (Iroquois), died age 28 and was buried with full military honors at the 2nd Presbyterian Church in Phila. All the city's clergy and a large crowd of citizens were reported as attending his internment on March 22. Named Ojikheta, he was a close friend and fellow soldier with Lafayette, who had him go to France and live with the Frenchman's family for over a decade. The chief's English name was Pierre Jaquette, in honor of the general. the March 27 edition of the Daily Advertiser had more, including the cause of death as pleurisy contracted on a long, wet and difficult journey to attend the government.

This large delegation of about 50 indigenous leaders were specifically invited to Philadelphia by Colonel Pickering, Superintendent of U.S. Indian Affairs. They arrived March 13, "under the immediate care of Doctor Samuel Kirkland." It was the contact that began an official treaty process,

specifically the Treaty of Canandaigua, for which Quakers were the official witnesses for both sides.

Notable Graves

Jesse George -Blockley (1785-1873) Member Philadelphia Mtg. Western district. An Orthodox Quaker, but buried Merion's Hicksite burying ground. He was donor of George's hill. Census 1840 and 1850 and 1860 Blockley. Owned Ridgeland in W. Philadelphia (Harvey)

Samuel J. Levick (1819-1885) worked for the abolition of slavery and was treasurer of the Junior Anti-Slavery Society when I was young. He was also active in several other anti-Slavery societies, participating in debates on abolition and supporting the free-produce movement. Secretly, he belonged to William Still's Vigilance Committee, which aided fugitive slaves coming into Philadelphia; served on both the Standing Committee and the Finance Committee.

John Roberts the Third (1721-1778)-hanged by rebels in 1778 For selling a horse to British troops during the Revolutionary War; member of Merion Meeting and wealthy miller whose

house still stands on Old Gulph Road near the intersection with Mill Creek Road.

Thomas Wynne (1733-1782)-member of Merion Meeting and fought in Revolutionary War for the rebels

Joseph Price (1753-1828)-member of Merion Meeting and carpenter, innkeeper and caretaker of the burying ground.

John M. George (1802-1887)-member of Merion Meeting who left money to found George School.

T. Thomas Zell (1828-1905)-member of Merion Meeting; grave diggers found a previous burial of bones in a sitting posture facing the West. The bones were straightened out and laid flat and then Zell’s body was put above them. These bones may belong to an Indian.

The oldest cherry trees lining the walkway through the burying ground were planted as a test before the same type (Yoshino) was donated to Washington D.C.

Today bodies must be cremated and only members are permitted, under the guidance of the Care and Counsel Committee.

This essay was researched and written by beloved member Mary Wood and updated by Janet Frazer in 2018.

Related History Pages

Philadelphia-Columbia Railroad

Title or short description

Burying Ground

Title or short description

Underground Railroad

Anti-Slavery / Abolition

Anti-Slavery/ Abolition

This page was written and researched by Janet Frazer, our archivist and historian and Mary Wood, who was a long-time member and archivist. Their sources she used are documented here.

Burial Record. Merion Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). Lower Merion

Historical Society. <http://www.lowermerionhistory.org/burial/merion/> (accessed 1/9/2018).

O’Donnell, Patricia C. “This Side of the Grave: Navigating the Quaker Plainness Testimony in

London and Philadelphia in the Eighteenth Century”. Winterthur Portfolio 2015 49:1, 28-55.

https://works.swarthmore.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1078&context=sta-libraries (accessed

1/9/2018).

Webster, Nancy. Email 1/22/2018.

Wood, Mary. “Merion Friends Meetinghouse”. The First 300: The Amazing and Rich History of

Lower Merion. Ardmore: Lower Merion Historical Society, 2000.

Patricia C.

O’Donnell, This Side of the Grave,” Wintertur Portfolio 2015 49:1, p. 47,

https://works.swarthmore.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1078&context=sta-libraries .

615 Montgomery Avenue (Activities Building)

653 Montgomery Avenue (Meeting House)

Merion Station, PA 19066